COVID-19 and Suicidality

- This article suggests multiple ways of minimizing suicide risk during the pandemic, as well as during its aftermath

- Suicide prevention is urgent during COVID-19 because the mental health of psychiatry patients, the general population and vulnerable groups is at higher risk in such a stressful time

In this section

This article by Gunnell et al. explores the reasons why suicide risk may increase as the COVID-19 pandemic spreads and provides suggestions for preventing suicide during this time. Suicide prevention has become increasingly important during COVID-19. Physical distancing, fear, and self-isolation are making life much more difficult for those with mental illness, as well as everyone else. Patients with psychiatric disorders may have worsening symptoms and others, especially those who contract the illness and frontline healthcare workers, may develop anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress, which are all associated with an increased suicide risk.

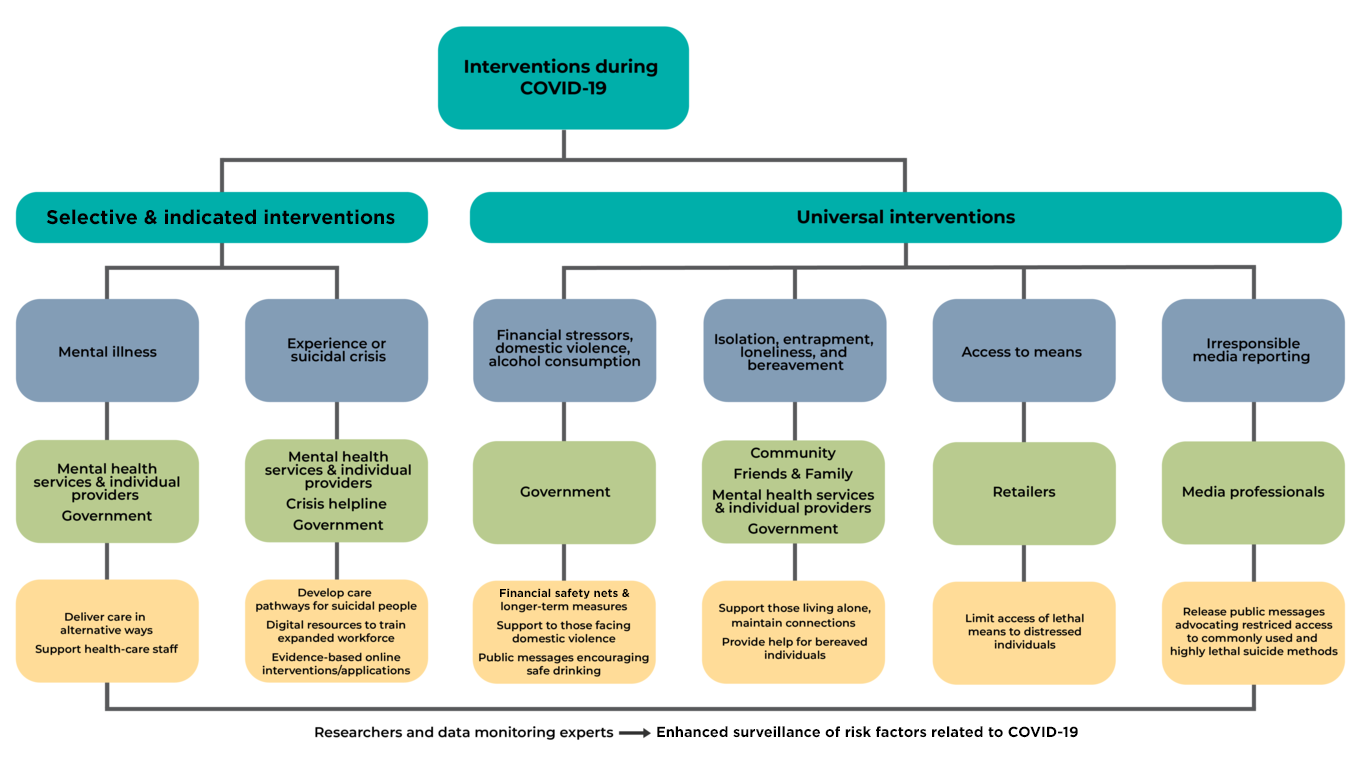

An increased workload and finding new ways to handle the COVID-19 pandemic is putting an extra burden on mental health services. Psychiatric assessments and interventions are being done via telephone or digitally by some services already, and should be implemented by others, keeping in mind that not all patients will be comfortable with such interactions. Psychiatric patients in suicidal crises may not seek help, out of fear that they might contract COVID-19 in an overcrowded service where they must meet a psychiatrist in person. Voluntary sector crisis helplines may be overloaded with calls and a decrease in volunteers. “Mental health services should develop clear remote assessment and care pathways for people who are suicidal, and staff training to support new ways of working.” Digital training resources can enable newly trained people to play an active role in helping those who are suicidal in mental health services and on helplines.

Unemployment and financial stressors are known risk factors for suicide and the article calls for governments to address this via financial safety nets such as unemployment supports, food, and housing. Educational institutions need to teach the curricula in alternative mediums and governments should offer them financial support if needed. Domestic violence and alcohol consumption, both precipitants for suicide, may increase during lockdown. Social isolation, loneliness, and entrapment also increase suicide risk, especially for bereaved people, therefore community support and easily accessible help for individuals living alone becomes very important. Access to lethal means that may increase suicide risk such as firearms and analgesics should be monitored carefully by retailers selling these products and temporary sales restrictions and messages about reducing access to common lethal suicide means should be applied by the government and non-governmental organisations. The media should be careful in reporting suicides, as the repeated exposure to crisis stories may increase fear and suicide risk. Therefore, COVID-19-specific guidelines should be implemented in the media, next to the existing ones.

The article suggests that researchers and data monitoring experts should provide an “enhanced surveillance of risk factors related to COVID-19 (eg, via suicide and self-harm registers, population-based surveys, and real-time data from crisis helplines)”. Overburdened mental health care providers should be monitored and supported with adequate resources. Moreover, resource-deprived areas may suffer worse effects from the pandemic and misinformation/stigma around COVID-19 may be worse in these areas. Risk factors in these poorer settings include the social effects of banning funerals and religious gatherings, vulnerable migrant workers, and interpersonal violence. The consequences for mental health in the entire population will probably appear for a longer period and peak later than during the pandemic itself. Research evidence, national strategies, and international collaboration should provide a solid foundation for suicide prevention.

Lancet Psychiatry

Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic

Lancet Psychiatry 2020 Published Online

April 21, 2020

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1

ADVICE FOR PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMSADVICE FOR PSYCHIATRIC SYMPTOMS

We often use the term ‘stigma’ to refer to any attribute, trait or disorder that marks an individual as being unacceptably different from “normal” people. The eWe often use the term ‘stigma’ to refer to any attribute, trait or disorder that marks an individual as being unacceptably different from “normal” people. The e

more…PREVENTING SELF-HARMPREVENTING SELF-HARM

Studies show that people with schizophrenia may be at high risk of attempting suicide. In particular, symptoms of depression, active hallucinations and delusionStudies show that people with schizophrenia may be at high risk of attempting suicide. In particular, symptoms of depression, active hallucinations and delusion

more…